Creating mind maps is a skill, and requesting it from students without preparation requires great care. Here are options for using mind maps with students, with a better knowledge of what you are doing.

At the end you will find a summary with the relevant ideas for you to apply the content, as an image and a PDF.

Why be careful

Making mind maps is similar to writing in some aspects, the most important being that it is a skill. As you may well know, no one learns a skill only with knowledge and understanding, it is necessary to train, and training consists of learning and then practicing.

I have seen more than once suggestions for teachers to ask students to prepare mind maps. Since it’s a skill, I’d be very careful about doing this; to say that making a mind map is simply about defining a theme and inserting topics and subtopics is like saying that writing is simple, just put one word after another and form sentences.

A text also has an organization of ideas that can cause confusion in the reader even if it has a good format. A mind map also has an organization of ideas. Some criteria for a quality mind map are:

- Synthesized topics, with minimal text, containing only one idea

- The levels of the mind map go from the most general to the most specific.

- Use context to eliminate text repetition (a topic is the context of its subtopics)

Just like writing, making mind maps has a motor and a cognitive component. The motor component includes what and how to do it, in an application or when drawing, depending on how you design it. The cognitive component involves thinking, including making assessments of quality and adequacy, among others.

So, imagine my surprise at something that happened. One late afternoon, I was walking randomly to unwind when I passed in front of a school, where there were two students. I had already passed when I had the inspiration to go back and ask them if they knew about mind maps. One of them said yes, that a teacher had given a test in which she had asked them to make a mind map, and she immediately explained what it was! Can it work? Yes, but in my opinion there is a risk that some students will not even be able to start.

Option: Pre-structured mind map

A simpler option here to start is to provide students with pre-structured mind maps, which students just fill in with content, preferably familiar.

A simple example and just to illustrate is the following mind map: for certain ages, it will be easy for students to think about or research cute animals and use a topic for each animal.

A great analogy of this approach is with forms: the field structure is there, and you just fill in the structure with your content.

Providing structural models for content is one of the elements of the Models & Methods approach, and it gave rise to our book Models and Methods for Using Mind Maps (in Portuguese), where dozens of models in various areas are described, complemented by methods when necessary.

Option: Examples

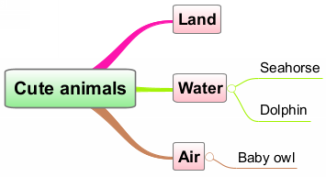

Another possibility is to provide mind maps, in addition to being pre-structured, containing examples of content, such as the one in the next figure.

Note that, in addition to indicating what the text of the topics is like, one of the examples suggests a more specific possibility to direct the search for content, "baby".

Option: Illustrate only

An even simpler option is to provide the mind map with text and ask students to illustrate it. This way they get used to the structure and content without having to think about something they haven't been trained for.

Option: skill breakdown

In a tennis class for beginners, the young teacher taught the technique of serving. He went to the correct position, served twice and addressed the class, saying: "Do it".

That was a "bit too much" for me: the initial posture, the movements of arms, legs, head and torso, not to mention the eyes, coordinated with a moving ball and still aiming a trajectory for the ball. I only know one person who, in order to learn motor skills, prefers to see the whole rather than the parts. That's a higher level of skill, an ability to learn skills, or meta-skill.

Meta-skill: the ability to learn skills.

I ended up leaving the area and went to train alone, and the first thing I did was take the ball out, so I could focus on the movements first. I also used a meta-skill technique, slow-motion: I slow down to learn the movement, and only after that I try to do it faster.

One principle of meta-skill is: one new thing at a time. Two or more new things can easily overwhelm students. A possible and serious consequence of this is when a student thinks that the problem is with him and generates some limiting belief about his ability, when in fact the problem is with the didactics.

Meta-skill principle: one new thing at a time.

And while it is still difficult, another option I have is the principle of segmentation, which is just a different name for divide-and-conquer: a technique is divided into segments and each segment is trained separately, and then their integration is done.

Meta-skill principle: segmentation.

Application to mind maps

Developing a mind map, as it is a skill with a motor and a cognitive component, can also be segmented. And the first segmentation is based on the fact that a mind map is a structure to house content, just like a spreadsheet. With this division, we can first work on designing the structure and then on editing the content.

Mind map = structure + content

In the case of hand-drawn mind maps, the drawing of the central topic is worked on first, then the others.

In the case of a mind map made with software, what I do is lead students to type anything, hitting the keys at random.

Only then is the content worked on. Images can also be a further step.

Work on structure, then content.

Criterion

What would be the best didactics to teach mind maps? Well, to begin with, this question does not seem very appropriate to me.

In my opinion, there is something more important than the structure, models, theories, rules, formulas and even methodologies: it is the adequacy of the didactic strategy to the students. Your starting point, as with anything you teach, is the student's current ability. For some students you can describe what to do, give some examples and then they can start doing it; others will need segmentation.

The basic fact here is that students learn by doing what they already know how to do.

You start with what the student knows how to do.

But you may be teaching groups of students with different abilities – an uneven group – and it is not easy, perhaps not even possible, to have a common starting point. That's why I call this situation of having uneven students one of the "hells of teaching"...

A possible solution begins by establishing assumptions about the students, that is, assumptions about what they will be capable of, tending toward the lowest common denominator. Then plan the activities based on the premises, observe the results and adapt the plan according to the feedback you get.

This approach could be called trial and error, but I prefer to call it more accurately the experience and feedback principle. In each cycle or iteration you will learn and progress, and you will inevitably achieve interesting results – if you have time, of course.

Iterative and progressive approach: experience and feedback.

Summary

Below is a summary of the content of this article in mind map.

Click here to download this mind map in PDF (132 kB).

Click here to download the original mind map (.easyx, 43 kB).

b

b