Organizing ideas in mind maps

Organize your thoughts and improve the quality of your mind maps

The issue of dealing with information overload becomes increasingly important. One of the options is to organize the information, and mind maps are a great tool for this. This article introduces two key concepts for organizing information and how mind maps can be better with them. Ignoring these concepts can cause mind maps to produce effects contrary to those desired.

At the end, a mind map is available summarizing the main ideas (on the page and for download).

The problem

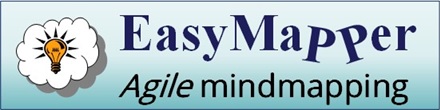

Look at the mind map below, about air and water

I'm going to work with the version below.

When we read a new mind map for the first time, we typically read the central topic first, which provides the context for the others, and then we read other topics. When I read the topic Composition, my first understanding was that it referred to the composition of water and air, which is the context provided by the central topic. But I felt the so-called cognitive dissonance, or confusion: the topic didn't align with the title, one wasn't consistent with the other.

It took me some time to identify that there was a quality issue in the mind map. The title is Air and Water, there is a main topic for water but not for air.

The topic Water has two subtopics and it is clear that Impurities and Purification refer to water, but what about Composition and Atmosphere? Assuming that they refer to air and inserting a main topic for this, we have:

To organize things, we typically have a structure and elements inserted or embedded in the structure. For example, your wardrobe has a structure of compartments and you put what you have in the compartments: dress clothes, sportswear, work clothes and underwear, shoes, socks, and accessories.

When a compartment is shared, you define virtual compartments or sections: pants section, dress section, shirt section, and so on.

The main principle of quality of an organization is "a place for everything, each thing in its place". The mind map does not have a place for everything and therefore has things out of its place. The result might be confusion in the understanding of those who read it.

Principle No. 1 of organization: a place for each thing, each thing in its place.

By the way, you may notice that the wardrobe pictured above has some violations of this principle with regards to shoes.

The example mind map has other issues of organization quality; I mentioned only this one to introduce an important problem that occurs with hierarchical structures in general and mind maps in particular. Resolving these issues is not obvious, in particular because, as far as I know, little guidance exists on this.

The purpose here is exactly to provide this instruction, in the form of distinctions that will enable you to see the anomalies of organization and correct them, thus preventing confusion for the readers of your mind maps.

You will also see how organization is essential to increase the power of thought, in the sense of being able to process more information in an integrated way. Let's start with a huge modern problem: the information overloads we have to deal with.

Information overload

Often you come across a lot of things of some kind. For instance:

- You may have too many clothes.

- On your computer's disk, there are hundreds of thousands of files, of which perhaps thousands are yours.

- In your WhatsApp and/or mail program, thousands of messages, there may be thousands more if you have a mail account at work.

- In the supermarket, thousands of items, of which you eventually buy dozens.

- In a search result, sometimes thousands and even millions of pages.

In addition, when performing certain activities, you may also be exposed and have to deal with a large amount of ideas:

- By attending a class, the teacher can introduce many new concepts.

- When writing a capstone project, you will have dozens of references, whether websites or works, which when read produce hundreds or thousands of ideas that you have to work with to achieve your goal.

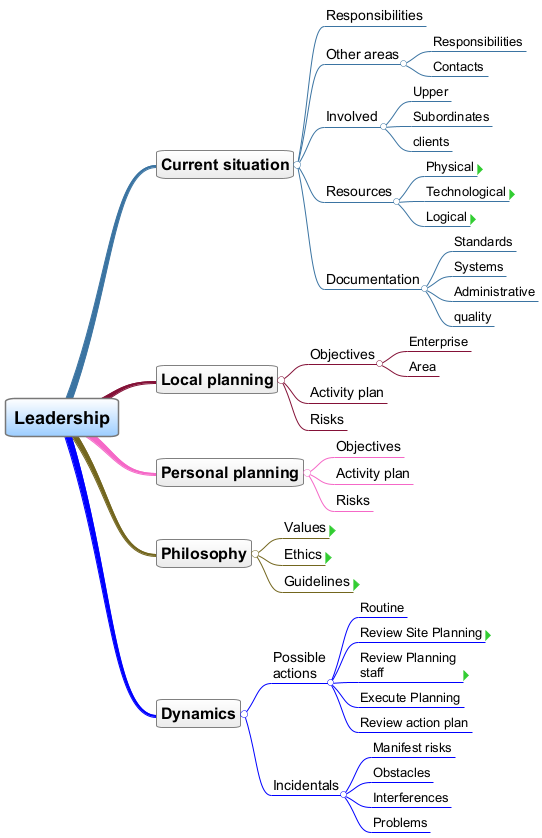

- If you exercise some leadership, you may be dealing with a multiplicity of objectives, people, resources, activities and other elements, which you must coordinate so that things work minimally well.

Limits

If we had absolute memory, fine: we would survey things and think about what was necessary without needing anything else. But this is not normal or expected; The fact is that we have limits to what we can remember and think at a given moment. We can easily remember three items that we have to buy, but not 100.

Obvious fact: our memory has limits!

These limits generate the risk of forgetting, more precisely of not remembering: something is important and is in our memory, but we do not remember it at the moment when it would be appropriate or opportune.

It is one thing to know, another is to remember at the right opportunity.

In addition, most of our information processing is subconscious; typically, we learn something to then use it later. When we are learning, we have to process new information more consciously, and the limit for this is stricter.

When this limit is exceeded, we enter so-called overload, and from then on it is more difficult to process any novelty. Education, as far as I know, doesn’t focus much on this aspect; I imagine you already have experiences of overload when attending classes.

Options

We have a few options for dealing with information overload. One is to filter information by relevance: of everything we receive, only a part is relevant to what we are doing and should be considered.

Another option is prioritization: among what is relevant, we assess that some information is more important than others and consider it first.

A third option is organization: we define blocks of information so that we can treat them separately. This is the scope of this article.

Organizing ideas

In the case of concrete things, such as clothes, what we do is group the objects according to certain criteria and store them accordingly. For instance:

- Dress clothes

- Sportswear

- Underwear

- Work clothes

- Shoes (day-to-day, party...)

This is what is commonly called organizing things. In addition to clothes, you already organize other things:

- files on your computer

- messages (bookmarking a message is an act of organization)

To organize things, we use ideas such as "dress clothes", "Biological Sciences", "Music", "Videos". A book will have parts, chapters and sections as elements of organization, each with its own name. A newspaper will have notebooks and sections, also with their names.

Each of these ideas that represents the whole is called an organizing idea. When you refer to "my clothes", "my shirts", my messages", you are using an organizing idea, you are dealing with concrete things as a whole.

Organizing ideas thus have a set structure: a container with a content, which are the elements (figure). The set has a name, which defines a criterion for proper insertion of elements. For example, a planet can be properly inserted in the "Planets" and "Cosmic objects" sets, but they do not fit in the "Plants" or "My things" sets. The name is a synthesis of the characteristics that the elements have in common.

Organizing ideas are sets: an idea groups other ideas.

They don't exist but they are useful

Organizing ideas are abstract, that is, they do not exist in physical reality, one cannot see, feel, hear, or pick them up. However, there is a good analogy with things from this reality.

In everyday life we use objects to group others - clips, boxes, bags, and packages. These organizing objects are analogous to organizing ideas; the difference is that organizing ideas exist only in the mind. Based on this analogy, you can think of organizing ideas as clip ideas or box ideas.

Organizing ideas and memory

An organizing idea has an interesting effect on the use of our memory. In general, words and other symbols function as access clues; for example, if I say "Your house," the immediate effect is that you remember where you live; that's part of the meaning of the term to you.

Incidentally, negation makes no difference here. For example, "don't think of your house" results in you thinking of it in the same way, because the presence of the clue is the determining factor. In this sense, commands such as "think" or "imagine" are not necessary either: "your house" is enough!

An organizing idea is a clue that potentially attracts several other ideas; for example, to understand "The songs on your computer", you think about your computer, the place or places where you keep music files and then the files, and you can even mentally "play" some of them.

An organizing idea directs our memory.

If there are many organized ideas, of course, not all of them will come. Test this effect by observing what comes to your mind to understand the terms "My favorite dishes." and "Decisive People in My Life"?

In addition, we can think with blocks of ideas and even make decisions, such as opening an "auto parts" or "underwear" store.

We can think and make decisions using an organizing idea.

This mechanism of access to memory can retrieve memorized information, but it also has a dynamic: on one occasion certain ideas may come, but on the next one others may. If you keep searching for information, you can also find more.

Classifications

Organizing ideas often occur in groups. For example, organizing your clothes requires several organizing ideas, such as "dress clothes," "sportswear," "work clothes," "underwear." The same applies to your files, emails, books, and dishes.

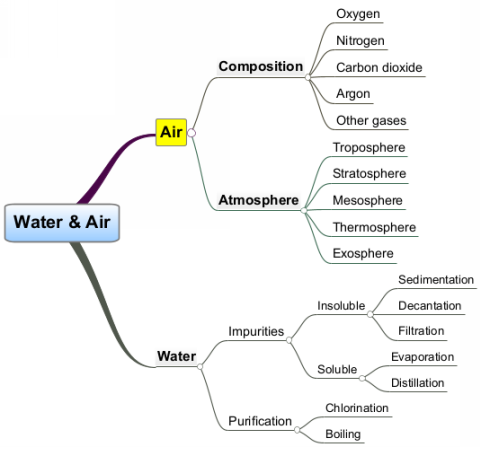

A set of related organizing ideas is called a classification. Science elaborates classifications to deal with large quantities, such as the classification of living beings. The sections of a website constitute a classification of its content. You have classifications on your wardrobes, your bookshelves, your desk, your computer. The periodic table of the elements is another good example of classification:

Multiple levels

Classifications can have multiple levels. A man's wardrobe, for example, may have the "Shirts", "Pants" and "Suits" subclasses in the "dress clothes" class.

The classification of living beings has numerous levels. Mathematics has, for example, algebra and geometry; it has analytic, plane and spatial geometry.

The analogy with objects also applies to classification; a bookcase, for example, in addition to open shelves, can have a closed section, with drawers and other compartments. You may have a desk with drawers, and each drawer has areas that constitute a classification. Ok, some drawers might only have the class "Miscellanea"...

As they are groups or sets of elements, classifications also have a structure. This is usually hierarchical, such as the classification of living beings and the folders on a hard drive, but there are other structures, such as the periodic table of elements.

A hierarchical structure has the desirable aspect of only having "down" connections, that is, it has no cycles or systemic connections that increase the complexity of the structure and thus make it more difficult to think about it.

Classifications and memory

We have seen above that organizing ideas function as clues to access memory. As classifications are sets of organizing ideas, when we use one, memory will be accessed by the set, and we will use the structure of ideas as a guide to locate information.

For example, suppose you want to listen to a certain song, which is in a file and you have no bookmark or list that includes it. You'll probably start from the My Documents folder, think of the My Music folder or wherever your songs are, and then look for the file by the beginning of the name. If there are subfolders with the name of each musician or band – an additional level in sorting – you could use the name to further filter the search. That is, of course, if you know the name.

Organization anomalies

There are several important issues related to the elaboration of classifications. First, the same set of elements can be classified in several ways; which is better?

In addition, a classification can have higher or lower quality. For instance:

- Classification may not have room for all elements

- An element may end up belonging to more than one group

Problems in classifications constitute organizational anomalies, which result in uncertainty and confusion in the reader's mind. For example, a white outfit can be classified as dress or work clothes: when it's time to pick it up, where is it? One website I saw had two sections: Ecology and Environment; there seems to be an intersection of ideas, and readers may have difficulty both looking for something and remembering where something they read was.

Organizing ideas and mind maps

Mind maps represent information and knowledge, and so are subject to many topics. It is then advisable to organize them, either by grouping topics with an organizing idea, or by elaborating a classification for the whole content.

Many classifications are hierarchical; as mind maps also have a hierarchical structure, mind maps constitute a natural resource to represent and work with classifications with this tree structure.

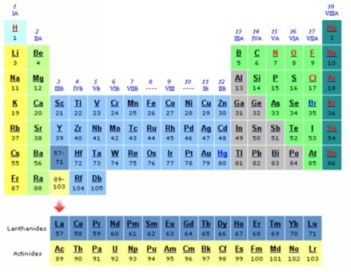

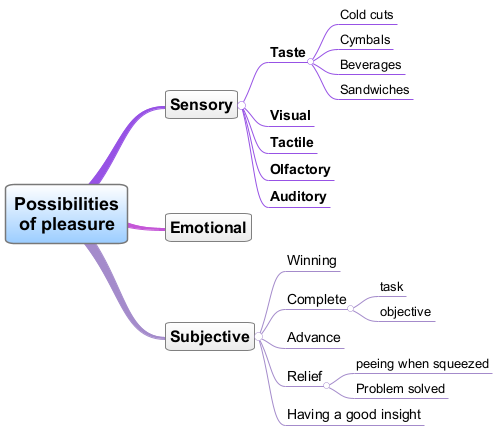

For example, the image below shows an excerpt from a mind map of possibilities for sensory pleasure. Note that the title represents an organizing idea, as do the topics in level 1 and the subtopics in the topic "Gustatory".

This mind map is in fact a part of another (below), which includes the pleasures we can feel - sensory, emotional (like joy), and subjective (like winning or completing a task).

Mind maps allow the mapper to think and work productively on hierarchical classifications and for the reader to quickly retrieve the meanings associated with the mind map.

Mind maps are structurally perfect for working on hierarchical structures.

In your own time, you can check the effect of the organizing ideas mentioned earlier. Look at a topic – for example, "Olfactory" – and notice how it stimulates you to access your memory.

In this way, working on the organization of ideas becomes an important activity in the process of making mind maps. At some point we may have to insert organizing ideas or revise them if they already exist.

In addition, all issues of quality of organizing ideas can occur in mind maps: a low-quality classification will confuse the reader and make it difficult to remember its content, to understand it and to use the mind map.

In fact, the risks of not considering the organization of ideas even include going in the opposite direction of one of the purposes of mind maps, which is to summarize and structure content in order to facilitate and give productivity to the assimilation and use of this content.

Application

Let’s take a critical look at a mind map from earlier in this article (reproduced below), in light of its organization.

An anomaly already mentioned is the lack of an entire branch for "Air", with an added effect of shifting what would be your items up and characterizing another anomaly of items at the wrong level.

Now consider the picture where it says "CO2": what topic does it refer to? It should indeed be on the topic of Carbon dioxide. This is an example of illustration organization anomalies.

Questioning - There are cases in which we do not detect an anomaly, we just question it. For example, why is the title/context of the mind map "Air and Water"? There is nothing that connects them that justifies this organization. Evidence of this is that this mind map could be partitioned into two, one for water and one for air, without loss of information.

Finding answers to questions about a mind map often depends on knowing who your target audience is and what it will be used for.

Using Structure Templates

Setting a quality classification from scratch can be very time-consuming. Thus, something that can greatly speed up the elaboration of a mind map is to find a ready-made classification or at least one that is close to the desired one.

For example, the mind map below is a possible classification of the information relevant to a leader. Consider what it would be like to get to this classification – or any other – without any starting point. If you are an experienced leader, you may arrive at it faster, but usually those who need to structure themselves are the beginners, who as a rule do not have enough content to be able to classify it – at the time when they need it most.

So what we want most as mappers is to find a good classification to use in the organizing levels of a mind map.

Possibility: to start from an existing classification.

It was based on this idea that I wrote an e-book called Models and Methods for Using Mind Maps (in Portuguese): providing models for the structure of organizing ideas so that a mapper has a starting point much closer to the destination.

And since organizing ideas not only block ideas but also attract them, a structure model also facilitates the retrieval of content, stimulating your thinking in the direction of retrieving information of the type of organizing ideas of the structure.

Check this out by reading the organizing ideas below and noting what they evoke in you:

- My favorite pleasures

- My best vacation

- My Experiences of Making Lemons with Lemonades

Summary

The following is a mind map summarizing the content of this article.

Click here to download the mind map in PDF (158 kB).

Click here to download the original mind map (easyx format, 4 kB)